Is there a formula for compounders?

Evolution suggests temporarily

Just before New Year, I finished reading The Compounders by Oddbjørn Dybvad et al., which describes the phenomenon of serial acquirers delivering exceptional shareholder returns over many years. I picked up the book because it was recommended on a podcast I listened to. Although I was skeptical, I read it with an open mind. Overall, I liked it and the book offers several great insights worth learning from. Here are my key takeaways and lessons learned.

Selection bias can fool anyone

I was not far into the book before my first critical thought hit me. There is clearly selection bias here, as the highlighted companies have all been great successes.

A mitigating factor, however, is that after reading the fifth case (Addtech), the book begins to carry a bit of a “The Superinvestors of Graham-and-Doddsville” vibe, referencing Warren Buffett’s famous 1984 article refuting luck as a major ingredient of his performance. Buffett’s point was that many value investors who applied Benjamin Graham’s principles, and who were part of Buffett’s intellectual network, consistently outperformed the market. That could not be a coincidence.

Likewise, the people involved in the Swedish serial acquirer cases presented in the book have cross-relations and have learned from each other. The five Swedish companies mentioned (Lifco, Indutrade, Bergman & Beving, Lagercrantz, and Addtech) have all followed roughly the same model, so perhaps there truly is something here.

Still, selection bias is a powerful force, constantly trying to fool us. It is rooted in our attraction to compelling stories like those once told around the campfire. We love great stories about entrepreneurs conquering markets or, as in this book, a group of companies achieving outsized success. But statistical significance is a high bar to clear, especially in adaptive systems and when phenomena are measured over long periods.

Arbitrage in private markets

As I read, I developed my own thesis about the broader pattern these companies fit into. In the chapter on Indutrade, we learn that the company typically pays 5–8x EBITA multiples. The public equity market values companies at 10–16x EBITA on average, so if your own valuation is at this level, then acquiring businesses at low EBITA multiples represents an attractive arbitrage.

This is essentially the same valuation gap that private equity firms have exploited for decades. I see the Swedish serial acquirers as perpetual, private-equity-like companies that intelligently recycle capital into this “arbitrage spread.” However, as more investors enter private markets, capturing that spread between private and public valuations may become increasingly difficult, leading to lower future returns from this strategy.

Reinvestment rate in an intangible world

The book defines shareholder return as the reinvestment rate multiplied by ROIC which a correct framework, but only if the incremental ROIC remains equal to or higher than that of the existing business.

The Swedish serial acquirers are anchored in the physical world, where this relationship is relatively straightforward. In the intangible world, however, the formula can break down, partly due to accounting rules and partly because of phenomena like network effects. Visa is a great example of this. It has an almost zero reinvestment rate but an astronomically high ROIC. Multiplying the two yields a near-zero result, yet the business consistently grows 10–12% annually, delivering extraordinary shareholder returns.

The magic lies in the network effects and branding, which create a compounding engine that requires very little reinvestment. Charlie Munger famously liked businesses with low reinvestment needs which runs counter to the ethos of The Compounders. This tension could have been explored further in the book.

The key behaviour for any business

After finishing the book, I reached a conclusion about what truly sets these companies apart. Yes, they cleverly exploited the gap between public and private markets, but they also share two distinctive traits.

First, everyone knows complexity and bureaucracy stifle innovation and decision-making. The companies highlighted in the book maintain decentralized operations and a relentless focus on costs. While many recognize this as a winning formula, the vast majority succumb to empire-building and poor decisions.

Second, while most business leaders know that ROIC is the key metric, and that strategy should revolve around the actions that increase ROIC and value creation, few actually run their companies this way. You can see this immediately as an investor in their reporting. Atlas Copco, for instance, demonstrates through its financial communication why it has been successful for over a century.

A company laser-focused on value creation and ROIC communicates this clearly; the rest are just storytellers navigating the dark woods without a light. The serial acquirers profiled in the book are all run with a ROIC- and investor-centric mindset, which makes a huge difference in decision-making.

Hyperbolic discounting

I will not dwell too much on hyperbolic discounting here, as I plan to revisit it in a later publication, but it is a fascinating concept introduced near the end of the book.

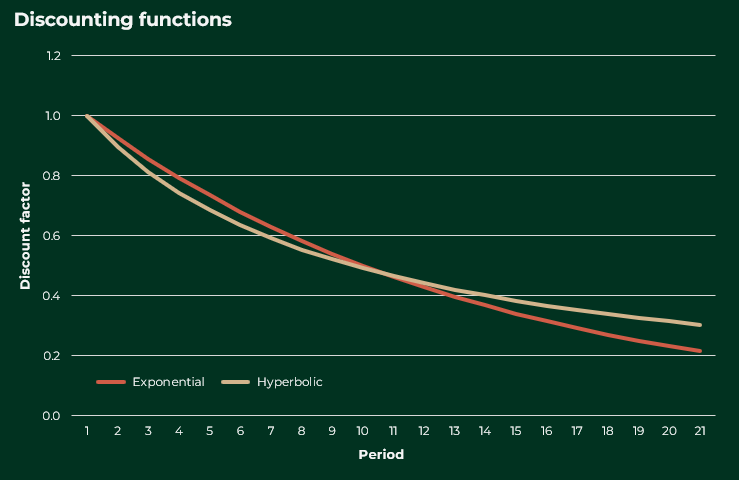

All financial models rely on exponential discounting, where the discount factor declines at a constant relative rate over time. However, behavioral studies show that human decision-making is time-sensitive. Hyperbolic discounting suggests that we, as investors, should be willing to pay a higher price for a truly long-duration competitive advantage than standard models would imply.

Is there a formula for compounding?

Years ago, I read Adaptive Markets by Andrew Lo, which presents the adaptive market hypothesis. This theory attempts to reconcile the efficient market hypothesis with behavioral economics. It’s a book I highly recommend.

The key insight is that markets are adaptive like biological systems. Certain “species” or financial strategies work for a time, attract imitators, and eventually lose their edge as competition intensifies.

The strategy pursued by the companies in The Compounders may have been well-suited to a specific era, but it might not work indefinitely as cheap private-market assets become scarce. Moreover, the approach could have nonlinear dynamics like beyond a certain scale of revenue or number of acquisitions, incremental ROIC may deteriorate fast due to complexity that can not be mitigated through a decentralized organisational design.

Long-term success cannot be captured in a static formula — not for businesses, investors, or species. Adaptation to changing environments is the ultimate driver of survival and success over time.

I forgot to touch on one topic and that is the decentralisation vs centralisation. The book favours decentralisation through these cases, but again it could be the selection bias that distorts our thinking.

Coming back to adaptation and dynamic environments, I don't think there is an optimal solution to this question. There are definitely industries and environments where a centralisation design delivers scale economies that the decentralised model can never obtain.

Thanks for writing this. Your selection bias insight is brillint.